So, the dietary guidelines have been updated...

- Kaydine

- Jan 15

- 6 min read

Last week, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans for 2025-2030 were published, sparking significant discourse across the nutrition community. In light of our recent “Built Environment” series here on the blog and the current realities of nutrition and food access in the U.S., it feels especially timely to unpack what these new guidelines mean.

Before we dive in, a quick history lesson for context:

The Dietary Guidelines are a set of nutrition recommendations published every five years by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The purpose of this guide is to outline the dietary patterns needed for optimal health and the prevention of chronic disease. An advisory committee of nongovernmental nutrition, medical and public health experts review the scientific evidence and use it to inform each update.

If you’ve been following the recent discourse, you’ve probably heard the familiar refrain that “no one pays attention to the guidelines.” While that may be true for much of the general public, the guidelines quietly shape far more than individual eating habits. They influence food policy, nutrition education and federal nutrition assistance programs like WIC and SNAP. They also guide the nutrition counseling provided by registered dietitians and other health professionals. The first iteration of the guidelines was published in the mid‑1890s, and they have continued to evolve alongside our food system, public health priorities and scientific understanding.

My first encounter with the Dietary Guidelines was in the fourth grade. The food pyramid was introduced in my science class during a nutrition unit. The food pyramid (Image 1) illustrated the major food groups and the recommended daily servings for each. The base of the pyramid featured the largest serving category, and the portions decreased as you moved upward (a visual cue for how much of each food group you were expected to eat). For example, grains occupied the widest section, while fats, oils and sweets were placed at the very top in the smallest segment.

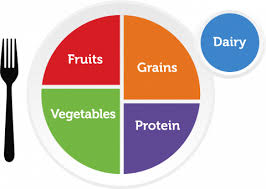

The food pyramid was discontinued in 2011 and replaced with a simpler, more actionable schematic known as MyPlate (Image 2). While the pyramid effectively highlighted the different food groups, it wasn’t always intuitive for the average person to translate those servings into what a balanced plate should actually look like and it was often critiqued as being to grain heavy.

The MyPlate schematic offers a clear, straightforward depiction of how to structure a meal to ensure adequate intake from each food group and support a balanced diet. Early in my nutrition training, I remember debates during my lectures about its limitations, particularly how the format doesn’t easily account for foods that aren’t “deconstructed” into neat categories. Think burritos, sandwiches or cultural dishes where multiple components are integrated. Even so, MyPlate remains one of the most consumer‑friendly illustrations we have for visualizing a balanced plate.

Last week, the USDA (under the new administration) released what they describe as “updated” Dietary Guidelines that will shape nutrition recommendations for the next five years. In this blog post, I’ll be breaking down these new guidelines and highlighting what’s solid, what’s superficial and what’s simply incorrect.

The 10 page document begins with a message from the secretaries outlining the rationale for the proposed updates. The language is notably forceful, leaning on bold, almost declarative phrasing such as:

"These Guidelines mark the most significant reset of federal nutrition policy in our nation’s history."

"Eat real food"

"We are reclaiming the food pyramid and returning it to its true purpose of educating and nourishing all Americans."

"Together, we can shift our food system away from chronic disease and toward nutrient density, nourishment, resilience, and long-term health."

"Better health begins on your plate, not in your medicine cabinet. The new dietary guidelines define real food as whole, nutrient dense, and naturally occurring, placing them back at the center of our diets."

"This is the foundation that will make America healthy again"

Now, if you’ve been paying attention to the state of public health over the past few years, or even the past few months, it’s hard not to feel frustrated by the sheer hypocrisy and hollowness of these statements. My issue with this kind of messaging is simple: talk of “real food” or professed “concern” for the nation’s health means very little when the structural barriers that prevent millions of people from accessing affordable, nutrient‑dense foods remain unaddressed. It means even less when funding for nutrition assistance programs serving low‑income families and children is being cut, or when health insurance premiums continue to climb. So the question becomes: what are we actually accomplishing here?

The messaging is laced with even more irony. They cite the rise in chronic diseases as a consequence of our reliance on processed foods (a term that describes some nutrient dense foods and is not exclusive to those considered unhealthy btw), yet make no mention of the social determinants of health that drive this trend. This omission is unsurprising as public health messaging in this country has a long history of blaming individuals for systemic failures rather than confronting the structures that perpetuate them. The reality is that telling people to “eat real food” accomplishes nothing if the environment remains unchanged and the deep‑rooted inequities embedded in our food system, and even our healthcare system, continue to persist. Additionally, they state that the downfall in public nutrition and rise of chronic disease is a result of inadequate nutrition research, and yet funding is increasingly cut for research. Make it make sense! I will credit them, however, for highlighting the importance of coordination across federal, state, local and private partners as a key driver of public health improvement. Furthermore, when scientists are meaningfully involved, the government is better positioned to make informed, evidence‑based policy decisions. That, after all, is the intended purpose of tools like the Dietary Guidelines. Whether or not the expertise of nutrition scientists was consulted in the preparation of these guidelines remains unclear to me at this point.

Let’s take a closer look at the recommendations themselves. Despite the claim that this represents the most significant reset of federal nutrition policy in our nation’s history, there is nothing truly revolutionary in these updates. In fact, most of the core recommendations remain unchanged:

-3 servings of vegetables daily

-2 servings of fruits daily

-3 servings of dairy daily

-Saturated fat should be less than 10% of total daily calories

-Consume less than 2300mg of sodium daily etc.

-Limit sugar

Honestly, there is nothing groundbreaking here...

They did include a section that highlights the importance of gut health and provided examples of fermented foods that can be consumed to support gut health. They also highlighted the importance of high fiber foods, which is very good, considering the fact that majority of Americans are not meeting the requirements for dietary fiber intake.

Here’s where the whole thing starts to veer into questionable territory:

The accompanying pyramid, which they claim “revolutionizes” the Dietary Guidelines and restores the pyramid to its “proper use,” doesn’t accurately reflect the recommendations outlined in the document. For instance, the flipped pyramid suggests that grains should be consumed sparingly, yet the text recommends 2–4 servings of whole grains per day (a category that is barely represented in the image). At the intake level implied by the graphic, it would be nearly impossible to meet fiber recommendations (which they didn't even mention). The entire visual feels arbitrary and counterintuitive, landing us right back in the same confusion that plagued the 2011 pyramid (how does this translate on the plate?).

The new DGA document itself reads as though a social‑media wellness influencer with no nutrition training had a hand in drafting it. At one point, they reference a supposed “war on protein.” Is the war in the room with us? Certainly not, in the current "gym‑bro" culture, where manufacturers are slapping “high protein” labels on everything from cereal to ice cream. The guidelines recommend 1.2–1.6 g/kg of bodyweight in protein, a notable jump from the long‑standing 0.8 g/kg recommendation. This range is often promoted in weight‑loss circles, yet the evidence supporting its superiority is limited, especially when you remove the confounding effects of simultaneous caloric restriction. The shift feels less like a science‑driven update and more like pandering to the cultural moment.

It is also glaringly ironic that the guidelines cap saturated fat at 10% of total calories, yet simultaneously encourage cooking with butter and beef tallow and emphasize increased meat and dairy intake. Following those recommendations would almost certainly push saturated fat intake well beyond that 10% threshold. The contradiction would be amusing if it weren’t so concerning. It raises real questions about whether any meaningful nutrition oversight went into preparing these guidelines.

Additionally, the guidelines recommend prioritizing oils that contain essential fatty acids, citing olive oil. However, the two essential fatty acids are alpha‑linolenic acid (ALA) and linoleic acid (LA), both of which olive oil is actually quite low in. Its primary fatty acid is oleic acid, which is health‑promoting but not an essential fatty acid. This makes the recommendation scientifically inaccurate and misleading, especially when oils like canola, soybean or flaxseed oil are far richer sources of essential fatty acids.

Only time will tell how these updated recommendations will affect our food system and policies. Based on the uproar this caused, I doubt health professionals will be compelled to incorporate these guidelines in their practice, and rightfully so. The fact remains that words are empty without action to support them. Nutrition and the state of public health requires oversight and interdisciplinary collaborative effort that depends on scientifically sound evidence to truly drive change that will actually benefit the public.

![Transportation and How it Contributes to Health Outcomes [The Built Environment Series Part IV]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/11062b_57bc41b37a1a4f90a215514e5a38b86c~mv2.jpeg/v1/fill/w_980,h_653,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/11062b_57bc41b37a1a4f90a215514e5a38b86c~mv2.jpeg)

Comments